Which is worse: surveillance or monopoly? And can one be used to destroy the other? That’s the question Cory Doctorow poses in “How to Destroy Surveillance Capitalism”. Illustration: Shira Inbar

Big Tech’s unrestrained harvesting of your and my personal data is not our biggest problem. The monopolies of Big Tech are. It is monopolies which really deprive us of our freedom and threaten our lives. So goes the message from Cory Doctorow in his new mini-book “How to Destroy Surveillance Capitalism”. He is on to something, albeit his conclusions are stretched a bit too far. Or not enough.

Instagram makes you depressed. Having cell phones in the bedroom get you divorced. Facebook is ravaged by Russian trolls, and YouTube’s rabbit holes pulls you into endless video streams of radicalized content. You’re trapped in the big tech giants ad-funded influence machine: they know everything about you, use it against you, and won’t let you go.

Two years ago, ranting like this would sound wild; today it is mainstream. Thanks not least to Harvard-professor Shoshana Zuboff, who in 2019 made headlines across the world with her opus on the “age of surveillance capitalism”, laying bare how the tech giants systematically harvest user data, aiming to guaranteed the outcome for advertisers and others who pay for it: that their messages will be not only seen but also acted upon.

However, not everyone buys into the surveillance capitalist narrative. Most recently, the Canadian / British author, blogger and internet activist etc. Cory Doctorow, who in his new some 80-page long essayistic book release, “How to destroy surveillance capitalism,” (read it for free right here), objects to some of the central tenants of Zuboffs work. Here’s where he’s right and where he’s wrong:

1. You are too much, Zuboff

Doctorow’s first blow is set against one of Zuboff’s notoriously sore points: her outspoken, but also somewhat high-pitched, rhetoric.

In Zuboff’s world, there are virtually no limits to how much havoc the technology giants can wreak. They are guilty of a lot more, than not misleading marketing and pulling unethical sales tricks. No, they, and their surveillance capitalism found a system that does not stop until it has gained full control over our lives, and where we are all reduced to willless individuals in a neo-totalitarian world order. She talks about “guaranteed outcome”, “Big Other” and about how we are all deprived of our “right to the future tense”.

Zuboff has been dazzled by the advertising industry and the technology giants’ own sales speeches. In reality their systems don’t work anywhere as well.

Doctorow objects. Yes, we are being monitored, and yes, we are being manipulated. But not to the extreme extent Zuboff wants us to believe. To him, Zuboff has been dazzled by the advertising industry and the technology giants’ own sales speeches. In reality their systems don’t work anywhere as well. Maybe one in 100 can be influenced to actually change his or her mind and act on it. A far cry from ‘mind-control’ or ‘brainwashing’.

In Doctorow’s view, it is not the automated behavioral modification of surveillance capitalism that is the biggest problem. Their monopolies are, he says. And offers three reasons for this being so.

2. Monopolies deprive you of your choices

As we all know, when you search on Amazon, you off course only see products from Amazon partner companies. Only products that fulfill Amazon’s content requirements and only from companies that both pay and generally behave the way Amazon wants it to.

When Apple sells iPhones to China, it does so without the possibility for Chinese customers to choose VPNs or encryption standards themselves. And when Facebook and Twitter find themselves with few real competitors, it’s because the two lock users inside their walled gardens, fiercely preventing new social networks from gaining ground.

All of this is caused by Big Tech’s monopoly-like nature. The ability of monopolies to deprive users of meaningful choices is the greatest threat to our freedom, Doctorow argues. Not the ability of technology giants to manipulate users to click, buy or vote in any particular way.

Doctorow’s points are compelling. Though I wonder if the monopolies’ deprivation of freedom of choice, and the manipulation of the surveillance capitalists, are in fact not quite as separated, as Doctorow would let us to believe.

3. Monopolies halt development and threaten civilization as we know it

The harmful effect of monopolies does not stop here. In addition to depriving us of significant choices, monopolies also halt technological development: alternatives from the outside are suppressed while the monopolies consistently develop themselves so as to make the largest profits, whether it makes users happy or not.

That’s why, says Doctorow, the way you read news on Facebook has largely not evolved since the mid-2000s, while the self segmenting Facebook Groups and advertising tools are so smooth and next-gen. Again good points.

However, the potentially most draconian consequences of monopolistic software development come from elsewhere: the build-up of “technological debt”, old code all to easily accumulated by IT systems as time goes by, putting virtual millstones around their necks and often poses significant security risks. This, Doctorow argues, is created by the same legislative mechanisms on which monopolies also rest: the legal regime, which, with the protection of copyright law and intellectual property, shuts down the free access to view, modify and improve computer programs, and which was created in the United States in the 1980s along with a number of other weakenings of anti-trust provisions.

Technological debt, more than mind control, he proclaims, poses the existential threat to our civilization and to our species.

Doctorow dreads what’ll happen when the day the technological debt is cashed in. And for this, not only Big Tech’s monopolies are in the firing line. Technological breakdowns can occur in every corner of our societies, from global shipping over food supply to pharmaceutical production. Technological debt, more than mind control, he proclaims, poses the existential threat to our civilization and to our species.

The Intellectual Property regime and its ills have always been one of Doctorow’s greatest fads. Here, however, he fails to really make his case, tying technology debt to his doom and gloom scenario.

4. Monopolies create an epistemological crisis, fake news and conspiracies

The weakening of anti-trust legislation in the US in the 1980s plays a significant part for Doctorow. The laxing of legal controls led to increased concentration in all industries, he posits, from banks, to oil, newspapers and theme parks. It led – along with the neoliberal wave of which it was a part – to increased inequality. And it created social and monetary ties and unholy alliances between legislators and capital that distorted society’s evidence-based, truth-seeking institutions and thus created – Doctorow goes on – a fundamental uncertainty about what is right and wrong and who to believe. An epistemological crisis, particularly affecting vulnerable groups.

This crisis is the material background for fake news and the success of conspiracy theorists. The monopolization, inequality and lobbying have created a world in which the manipulations of surveillance capitalism can frolic.

Doctorows musings in this way constitute a standard neo-liberalism-critique, only slightly twisted. But while neo-liberalism certainly can be attributed with at least a part of the blame, Doctorow doesn’t manage to fully convince me about the extent to which this is true.

5. Fight monopolies with competition policy

For all these reasons, monopolies must be fought, says Doctorow, to truly combat surveillance capitalism. This is the crux of the book’s title: To destroy Surveillance Capitalism, you must destroy monopolies as well.

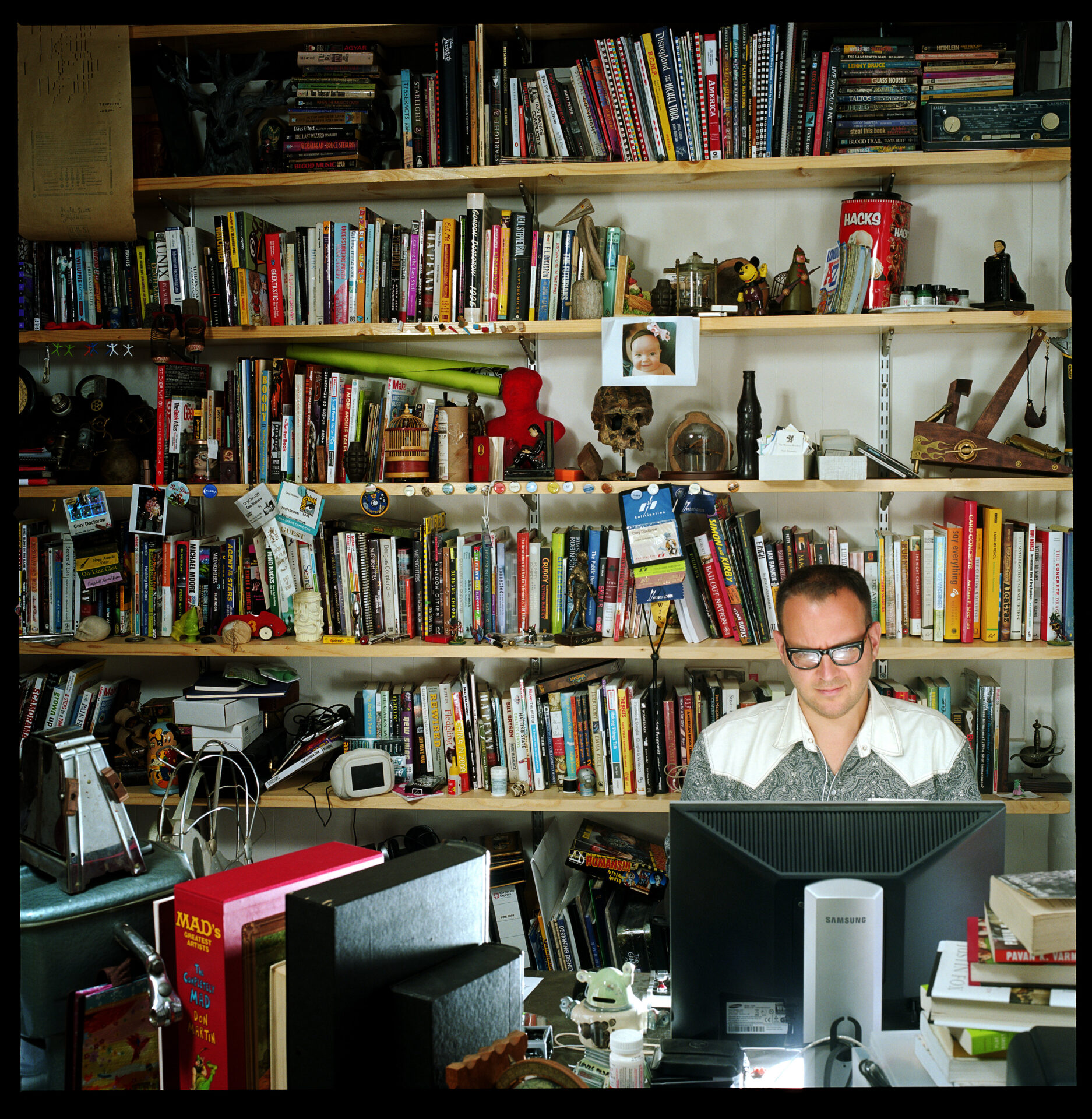

Cory Doctorow. Photo: Jonathan Worth (some rights reserved).

This can be done in several ways. One is to regulate monopolies much stricter than today. Ie.: don’t allow large firms to merge, don’t allow large firms to acquire small would-be competitors and put an end to platform firms competing directly against the firms that depend on their platforms.

Doctorow wants the classic anti-trust competition policy reintroduced in the US. That sounds like a good idea.

6. Open up

Doctorow, as mentioned, is not too happy with strictly enforced copyrights as these all too easily lead to the build-up of technological debt. But this is not the only problem resulting from the lack of openness. Closure is also detrimental when competitors refuse to let their products and services work together.

It’s a good thing that anyone can make a light bulb that fits to your light socket, and it’s bad when your printer doesn’t accept “foreign” ink. A good thing, that you can choose who you want to call, no matter their operator, and it’s bad, when Facebook locks you into using Messenger to talk to your friends.

Closeness – or lack of interoperability – is one of the tricks monopolists use to keep others out and down. That needs to be done with as well.

7. Share data

For some reason Doctorow never really gets specific on what exactly is needed to create interoperability. However one initiative with direct ability to stop, or at least slow down the surveillance capitalist data-cirkus, calls for attention: figuring out how to organize and safeguard the ownership of personal data.

If I own the information about who my friends on Facebook are, I could allow the apps of my choosing to use my Facebook friends list as their phonebook as well. This would make it much easier for me to use Apple’s iMessage or Signal or what have you, dismantling the artificial barriers erected around Facebooks walled garden, and voila, the monopoly would be much more easily broken.

The same is true in a variety of other contexts: If I own the data about what topics I’m searching for, what music I listen to, what movies I watch, what news I read, what shirts and socks I buy and what pizzas I eat, if I own all this data, I can also pass it on to the music, film and news services etc, which I like the best, and they could use all this nice data to give me even better music and movie and pizza recommendations, and thus allowing them to engage in data driven product development without having to try to capture me and milk me for data first.

For some reason Doctorow never really gets specific on what exactly is needed to create interoperability

Such data openness would obviously be good for the technology giants’ competitors and bad for the technology giants themselves, because the data openness would deprive the technology giants of the aces with which they trump every game: the gigantic data file which no one but themselves have at their disposal today, which is key to their earnings, and which new competitors will never, or only with extreme difficulty, be able to build themselves.

It is exactly this openness that Doctorow calls for. But he does not link it to the question of who owns what data. On the contrary, he denies that data can be owned at all.

8. Can facts be owned? Can data?

“Ownership of facts is antithetical to human progress,” says Doctorow. That sounds captivatingly rational. I myself subscribe to the truth as a principle. It’s hard to solve anything if the knowledge of what the problem is about, or what it takes to make a solution that actually works, is locked up by someone somewhere.

In addition, Doctorow points out, there is also something linguistically strange about the problem. How can one own facts at all? Do I own the information that I am my mother’s son? Or is it my mother who owns that knowledge? Is it both of us? And what about my father?

Both of these objections rings somewhat hollow. You can be rational and make progress without knowing all the facts. Just as long the facts you do have are essential and true.

And of course, information can be about, and in that sense also “owned”, by several different people at the same time. But that does not prevent me from wanting to decide for myself if Facebook, for example, should know who my parents are and which purposes Facebook should be able to use that knowledge for. Just like both my dad and mom should be able to decide if they want their identities linked to this data point or not.

9. The chicken and the egg

The main thesis of “How to destroy surveillance capitalism” is that it is the monopolization itself, not the rapidly developing Surveillance Capitalists, that is the real villain. That surveillance capitalism is just the latest example of the misfortunes propelled by monopolies.

Monopolies create problems no matter the industry, Doctorow believes. “Tech exceptionalism”, as he refers to, is not his cup of tea. Tech is neither born super-good nor super-evil. And that’s the part of Zuboff and her critical capitalism critique that he has the hardest time with. She overestimates what technology can do.

The real question, therefore, is not which of the two – surveillance capitalism or monopoly – is the worst. Who is hen and who is egg. The question is how best to combat them. Both. Together.

But Zuboff may well be right, even if her future scenarios might be a little over the top. Surveillance capitalism may well produce a world ruled by data harvesting and manipulation, even if it does not mean that we are all totally brainwashed. “Minor offenses” to our mental well-being and corruption of political processes can easily do.

Add to this, surveillance capitalism is in itself a winner-take-all game. The one with the most data to feed into his or her algorithms creates the best data-driven services – both for users and advertisers. Therefore, the big ones get bigger; the dominant will dominate even more. In this way, tech is actually exceptional: it’s a monopoly machine. Lax laws might create monopolies no matter the industry – also in tech. But tech also creates monopolies in and by itself.

The real question, therefore, is not which of the two – surveillance capitalism or monopoly – is the worst. Who is hen and who is egg. The question is how best to combat them. Both. Together.

This blogpost was first written for and published by Kommunikationsforum, where it is published in Danish.