Huawei, and by extension the Chinese government, wants to safeguard the future of the internet, making it better suited to handle the demands of tomorrow’s holographic online experiences, self-driving cars and other like scenarios. The intended enhancement is to be brought about by making the core IP protocol, on which the entire internet runs, far more “intelligent” than it is today. However, the change will also enable increased online surveillance and control. A feat all to well known and all too heavily practised by Chinese authorities today.

You should never turn on the light before dawn. At least not if you live in the Xinjiang province of China, and it’s in the middle of Ramadan. Doing so only all too easily lets the local police guess what you’re really up to: You’re eating breakfast before the day’s fasting starts. Which in turn makes you a practicing Muslim. And thus self-written for a trip to one of the infamous Chinese re-education camps.

It is Maya Wang who over long distance telephone tells me about the acidic paranoia that prevails in the westernmost part of China. A paranoia that is unfortunately based on hard facts: In Xinjiang alone, over one million out of the province’s total of 23 million inhabitants have already been detained.

Chinese Surveillance, manual style

Maya Wang knows what she’s talking about. She is a senior researcher and China expert at Human Rights Watch. Together with the German security company Cure 56, she has reverse engineered the surveillance app that Chinese authorities use to register the people of Xinjiang.

The study shows, among other things, that people are flagged if their electricity consumption is suspiciously high, to often enter their homes through their back door instead of the front door, or if they are thinking or believing strays too far from the orthodoxy of the state. Information that for the most part is logged manually by the provincial police.

“The work pressure is unsustainable”

Maya Wang, senior researcher, Human Rights Watch

The intensive surveillance is caused by the Beijing government’s animosity towards could-be emerging independence movements. And the people of Xinjiang really do stand out. They are Muslims, not atheists. They do not speak Mandarin like almost all other Chinese. And their looks are different, too.

“I do not know exactly how the police know how much you go in and out the back door, but somehow observers must be entering the records into the app” says Maya Wang, and continues “During Ramadan, observers actually lie in wait outside in the wee hours to see if you turn on the light. And a special unit with over 1 million observers stands by to physically move in with people and observe whether they behave suspiciously in everyday life. For five days at a time. And with revisits after two months”

From the observers’ point of view, the work pressure is unsustainable. Police officers with bloodshot eyes work from dawn until into the night. But also from the state’s point of view, the situation is far from optimal. The greater the workload, the more the quality of the manual monitoring decreases. “The observers simply often simply takes the easy way out”, says Maya Wang.

Scary proposals

“Some of this is very scary.” I’m on the phone with Mirko Presser of Aarhus University. He is an associate professor at the Department of Business Development and Technology and part of the management of Next Generation Internet, an EU program that supports the development of an Internet built on privacy, participation and diversity. It is not the physical surveillance in Xinjiang that he is alluding to with his comments. What scares him is something else: a proposal from Huawei for a so-called “New IP” – a new version of the Internet Protocol.

“Some of this is very scary”

Mirko Presser, Associate Professor, Aarhus University

Mirko Presser is not alone in his concern. He is joined by a host of others, sounding the alarms over Huaweis’ proposal since it was set forth earlier this year. The fear is that “New IP” will provide states – like the Chinese – with a new set of handles to more easily control who does what online. “The leaky global internet remains frustrating for Chinese censors, and they’ve dealt with it at great expense and effort,” James Griffith told the Financial Times in March. “But if you could make those problems go away almost completely by using a more automated and technical process, perhaps like New IP, that would be fantastic for them”.

James Griffith is the author of “The Great Firewall of China”. Here he also tells the story of Huawei and the Chinese government, which for most practical purposes are tightly interconnected.

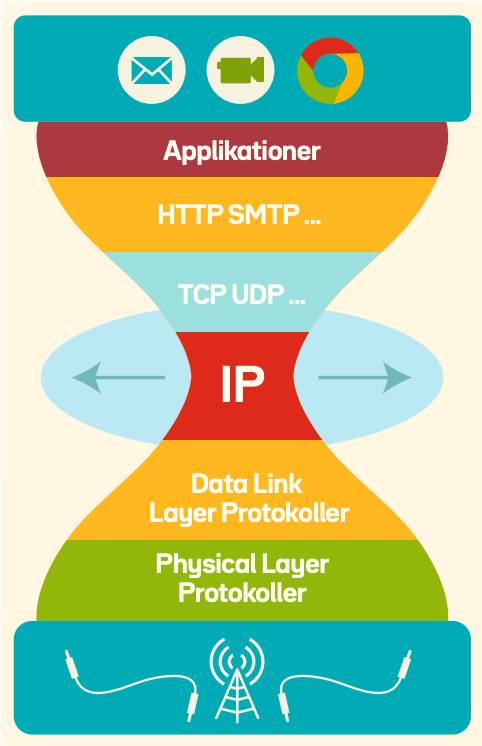

The beauty of the “slim waist”

The Internet or just IP protocol, which Huawei’s proposal is all about, occupies a small but central position in the larger TCP/IP protocol stack. In visual representations the TCP/IP stack is usually depicted as an hourglass shaped form, with the IP as the “slim waist” of the figure: The IP ensures that data being sent and received by your browser, email client or other applications knows where to go when transmitted to the network of cables, mobile towers and satellites.

The IP-protocol resides in the middle of the TCP/IP stack, and forms the stacks “slim waist”.

And it is precisely the prospect of this slim waist becoming much thicker that worries Mirko Presser and the critics.

As of today, the IP protocol reveals very little information about what actually goes on, when data packages are labeled for distribution in the network. The IP addresses entailed in the labeling tells the network where to find the recipients, but does not disclose information about who the recipient really is. And if you want to know what’s actually being communicated in the stream of data, the IP protocol isn’t of much use either: for this you’ll have to bother snatching up and looking into the data packages themselves, package inspection style, a feat which is technically doable but also tedious. All this is what the “New IP”-proposal wants to see changed. Both the IP address and the IP header need to be made much more intelligent and contain much more information.

“The proposal will consolidate a lot of things up in the IP protocol, which today are at lower or higher levels of the TCP/IP Stack. It makes the IP layer fatter, says Mirko Presser.

The proposal also signals a shift away from the so called “net neutrality”, which relies on the IP protocol as a neutral instance, ensuring that data can be sent around without anyone being able to discriminate on the basis of who is communicating or what they’re talking about. And contrary: With “New IP” network operators are given more power to assert control and censor – or as the New IP proposal prefers to say: prioritize – the traffic. The latter, prioritization, is something Huawei cares deeply about.

Huawei’s futuristic dreams

In a few years, surgical appendectomy will be performed remotely, with a doctor in one end of a special video-conferizing-like setup and the patient and a surgical robot at the other. All cars will move themselves autonomously around our cities. And when you hold video meetings, you’ll be able to see, feel, smell and taste everything going on. This is roughly what Huawei’s future scenarios look like, as hinted, eg, in this presentation, pitching the need for the New IP.

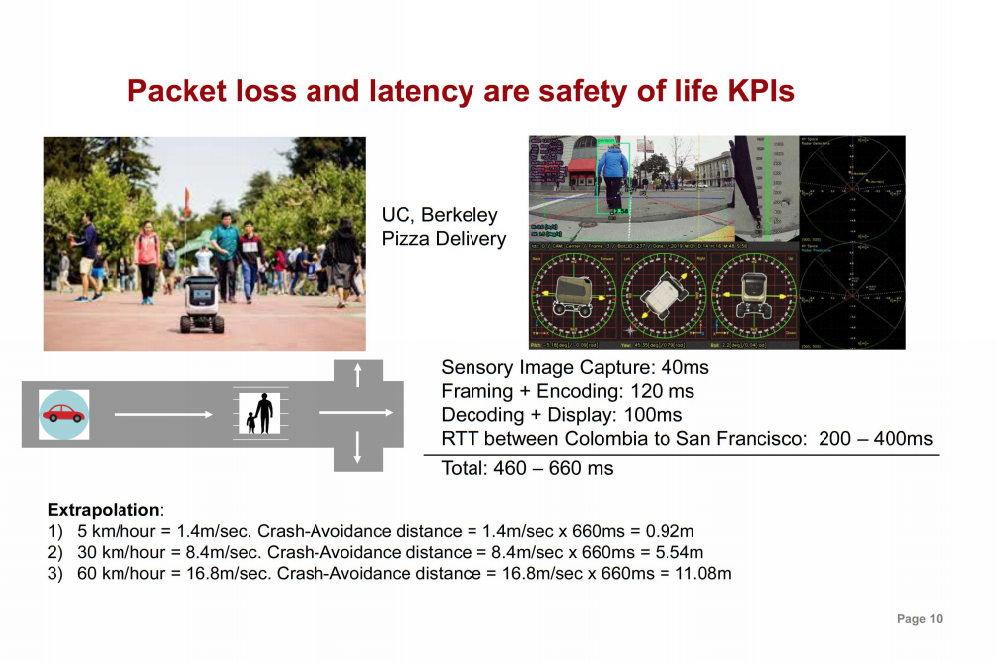

Not only does telemedicine, autonomous vehicles, the Internet of Things, holography and the tactile internet require huge amounts of data to work. They also demand data to arrive on time: The self-driving car must be able to pick up and react quickly to the smallest signals from the surroundings. And it is crucial that the surgeon’s scalpel does not lag when the critical incisions are to be made.

With the present delay in data traffic a car running 60 km/hour needs 11 meters for crash-avoidance. This can be minimized if New IP is adopted. From Huaweis presentation on future internet usecases.

In the future, therefore, data packets should arrive on time, with delays in the range of a single or two milliseconds. Not twenty or eighty, as today. For that to happen, Huawei argues, the network’s data packets must be able to be routed quickly and efficiently. And it must be easy to tell if a specific data package is highly time-sensitive or not.

Huawei’s argumentation is based on sweet and techy futuristic dreams. Not, of course, on notions of politically motivated surveillance.

Two tenets

Overall, Huawei’s New IP proposal is somewhat fluffy. In addition to the powerpoint-pitch, it consists of a two-page presentation for the process, a larger background presentation and a scientific 5-page document. Hardly a bulletproof playbook for turning the internet upside down overnight. Nothing is settled yet and there is yet plenty of room for the proposals to be both changed and expanded. But even as it stands, the proposal is not entirely without substance.

For one, the proposal opens up for network administrators to build their own functions and variables directly into the header and thus make the header much more intelligent than it is today.

This will enable the network to evaluate a query based on the header alone, without having to dig into the actual content of whatever is being transmitted. For example, Huawei writes, a header could have the function “forward before deadline”, which could then have the time of the deadline as a variable. Or the function “collect queue depth along the forwarding path” with the queue depth as indication of the level of congestion as the variable. Such features would provide information and intelligence to the network that would allow traffic to flow much more tailored.

While these two examples seem both innocent and beneficial, other functions may not have the same benevolent character. On the contrary: One might just as well create hardcore censorship functions, automating discrimination at the core protocol level.

Adding to this, the first octet of the IP address – so the proposal goes – should be reserved to indicate the user ID and declare what type of data is being transported, giving the proposed IP-functions more information of the datastream to work on – making it possible to prioritize the traffic in even smarter ways. Now, the proposal is pretty vague as too the question of which kinds of users this ID-process should address. It could refer to company entities. But it could also refer to individuals, in which case introduction of the New IP would be akin to putting your social security number on all messages you either send or receive on the internet. Likewise the nature of the type of data to be declared in the IP address is unclear. But again, potentially this could serve as a tool for automatic sorting of content.

Stumbling blocks are easily removed

This is where New IP causes critics to worry: The new, flexible IP only works because a unique user ID is stamped into each individual data package, every time a user sends or requests this or that piece of information on the internet. And because each data package is also to be forced to tell what it’s all about, laying bare not only who communicates, but also the nature of their communication. In effect New IP potentially empowers the network always to know what you are doing – and consequently enable admins to step in and intervene, if for some reason they decide your communications shouldn’t be allowed.

Before New IP can be used as a fully automated potential surveillance tool, however, a few steps must be taken first. First you must deal with authentication – the process of the network being able to determine who you really are. If you’re only known by your anonymous user ID, only this much harm can be done.

This obstacle does not, however, pose much of a challenge. In several countries telecommunications providers require you to show your ID-card in order for you to purchase the SIM card connecting you to the internet. China doubles down on this, requiring your face to be scanned in the proces, and coming down hard on anyone caught using borrowed or a foreign, non-Chinese, cell phones.

China doubles down on this, requiring your face to be scanned in the proces

Another stumbling block for the New IP to work on a massive scale is speed of deployment. For New IP to be effective, all the devices, routers, DNSs and gateways, which makes up the internet infrastructure, must be updated and/or replaced. If left all to itself New IP won’t cause much damage. Deployment, off course, can be a lengthy process.

For example, more than 20 years ago the IPv4 protocol was scrapped in favor of the newer IPv6, and yet IPv6 is nowhere near being fully rolled out on the market. According to Google, IPv6 adoption varies greatly across the globe. Countries like India tops the list, while others – as my native Denmark – only 3,6% of users access Google over IPv6.

In some markets, like my native Danish, as little as 4 percent of the internet traffic uses IPv6, according to Google. Apparently users haven’t yet felt the need for them to change their existing cell phones and network hardware to IPv6-enabled variants.

In China, where rollout is not as dependent on market needs, the situation is different. For example, the Chinese government has decided that IPv6 should be fully rolled out by 2025. The same could happen to New IP.

No smoking gun

Not everyone shares Mirko Pressers and James Griffith’s concerns about the New IP proposal. “The proposal is still too loose to be taken really seriously at all”, Milton Mueller, professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology and an expert in Internet Governance, tells me over the phone. “There are a lot of interests at stake in this discussion. Both strategic competition and military tensions come into play” Mueller continues, urging calm. “ I do not think Huawei is a tool for the Chinese government here. For Huawei, it’s mostly about their own commercial interests in the battle for the global market. They are super dynamic. And all companies try to set the standards themselves” he says.

Longtime telco pundit Torben Rune backs him up. “There’s nothing in the proposal which really makes the warning bells ring. Already today, you’re able to guess a lot about the traffic, if that is what you want. Based on the package size of the Netflix movie you stream, for example, you can figure out what it is you are watching, says Torben Rune. “There’s no smoking gun”.

“There’s nothing in the proposal which really makes the warning bells ring”

Torben Rune, Telco Pundit

Trying to pinpoint exactly where and how the New IP proposal misses the mark, even the critics get a little vague in their speech. “I can not point to a precise section of the proposal. It’s too imprecise with too many buzzwords”, says Mirko Presser. “But I can see that Huawei will introduce a tighter control of traffic. And it breaks with the basic idea of freedom on the web that lies behind the IP protocol. That no one, not even governments, should be able to interfere in what you say.”

Technical details aside, one more thing fuels the suspicion that something ill-intensioned is going on with the New IP-proposal: The question of who is to decide if and how New IP should be adopted. Here Huawei’s choice of ITU, the United Nations Organization for Telecommunications, has caused eyebrows to be raised.

ITU vs. IETF

ITU is the UN body which dates its history longest back in time. Exactly to 1865, when it was created to handle the wire-cable explosion created by the invention of the telegraph approx. twenty years earlier.

After the telegraph came the telephone and the wireless networks. Today, the ITU is responsible for coordinating standards such as X.509 (cybersecurity), Y.3172 (machine learning) and H.264 / MPEG-4 AVC (video compression). The Internet itself, on the other hand, has not traditionally been ITU’s area.

Instead, standardization bodies such as the IETF – Internet Engineering Task Force – have been responsible for the work. In the IETF, governments aren’t deciding, as it is in the ITU. Instead industry professionals drive the process. A highly technical approach.

By virtue of its industry dominance, countries and governments don’t really have much of a say in the ITU – as opposed to the large, predominantly US-based tech companies. Russia, China and a number of other countries have complained loudly about this in recent years. They want deciding power as well.

But in an IP context, they’re ridiculous

Mirko Presser, Associate professor, Aarhus University

It is against this background that Huawei chose the ITU and not the IETF as the battleground for their new proposal. “But ITU is not a good place to have that debate” says Mirko Presser. “Governments shouldn’t be deciding this kind of things. It is safer to stick to the IETF”. Presser fears the IP protocol will be taken hostage. That those who muster the most allies behind their political interests wins. Not those with the best arguments. As a result technological development will be sidetracked, dictated by political parties.

Fundamentally Mirko Presser is not at all convinced the IP protocol needs to be changed in order to deal with the challenges of the present Internet development. “Huawei even points to the need for 1 millisecond delay in communication” explains Mirko Presser. “But here they encounter quite physical limitations, which have little to do with IP. For example, for 1 millisecond delays, the server must not be further away than 300 kilometers from the app interacting with the server, in order not to break the laws of physics and the speed of light. Here, the solution is simply to move the server closer ”, says Mirko Presser and continues: “Several of the things that are part of New IP are already being researched in many other places. For example, semantics, new ways to route and security, which all, in and by themselves, pose interesting problems. But in an IP context, it’s ridiculous. They break with the idea that a business cannot own or control a network. But surely telecom operators would like them to come true”.

At the time of writing, the future of the New IP proposal in the ITU is unclear. The paper was to be considered at a large-scale meeting in Hyderabad, India in November, but it has been postponed due to corona, without a new date being added to the calendar. And even then, it can take a long time before a vote can take place.

IP in the Great Firewall

Fortunately for Chinese police and authorities their surveillance of the Xinjiang Province is not purely manual. The province, says Maya Wang, is littered with surveillance cameras, and the public spaces are filled with automated checkpoints which automatically scan and match your face, your ID card and your devices. On the doors of residence houses QR codes reveals the names and personal records of those living indoors. When you refuel your car, your ID card and car registration number are matched to see if everything adds up.

The system behind is called IJOP – Integrated Joint Operations Platform. “It does not seem that IJOP is connected to the big firewall” says Maya Wang with reference to the system, which to the best of its ability blocks sites and apps and controls who can see what on the web. “At least not yet”

The question is whether it soon will. And if so, whether New IP will be used to tie all the many bits together.

This blogpost was first published in Danish in the September 2020 edition of Prosabladet (click to read the entire magazine, a portrait of Mirko Presser and a nice infographic explaining the New IP visually).